No-one will forget the distraught look on Nathan Brown's face as he gripped his left shoulder after a grab at Panther Dean Whare's jersey a week ago.

It seemed an innocuous 18th-minute tackle attempt, but it had devastating consequences. The Eels lock had torn his pectoral muscle, which is normally a minimum three-months on the sideline.

"The last few players we broke the news to were certainly quite emotional once they found it," said former Roosters club doctor Ameer Ibrahim, who retired after the 2018 Telstra Premiership win.

"We had one a year for the last five years at the Roosters."

The NRL's injury surveillance report showed there were 10 pectoral injuries in 2017 and nine in 2018. From that 19, five were in pre-season training and one was in the NRL Women's competition.

It is such an unwanted injury because it is means a long-term absence.

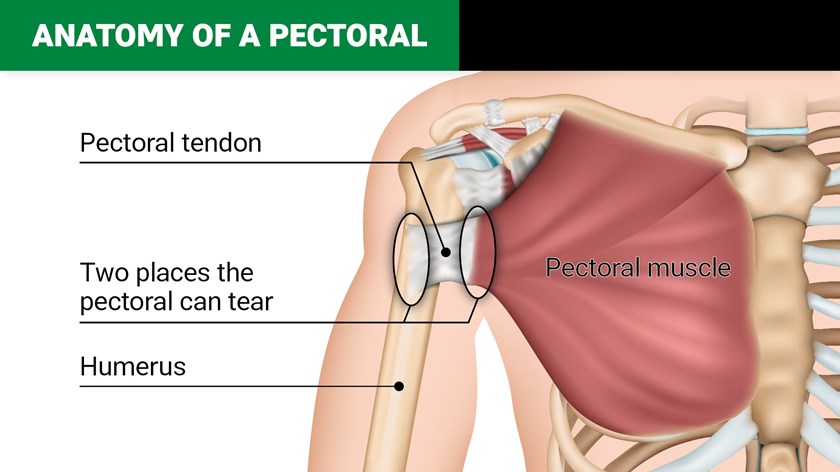

Most people think it is a tear in the large chest muscle across the upper body. In actual fact, it is a tear at either end of a tendon that connects the chest muscle to the humerus, or upper-arm bone.

If it tears at the muscle's end, often with rest and rehabilitation the time missed is not as lengthy and depends on the grading of the tear. But if it tears at the bone end it requires surgery.

Dr Ibrahim said players who suffer a pectoral muscle tear need not worry about any weakness being there permanently.

"Provided you rehab it the right way," he said. "And the surgical techniques they use now is they infiltrate the tendon into the bone and lock it off on the other side of the bone.

"So it's quite strong – probably stronger than the surgery with the make-shift tendon.

"You need to give the body good time for the tendon and bone to integrate. At the Roosters we worked on getting them back after 70 days – so 10 weeks. I've seen other clubs do eight weeks.

"You can push the envelope but sometimes it depends on the player's position and how much tackling he does."

And tackling is the culprit – the reaching out to grab an attacking player motion. That does the damage.

"When someone is moving at say 30km/hr and runs past you but you grab at them, that lever is too long and that tendon takes the trauma," said Manly's head trainer Don Singe.

It is such an unwanted injury because it is means a long-term absence

"It's not always a reflection of fatigue or on pre-season training. It's just a really unfortunate situation that happens in an instant."

Singe says rugby league players are ultra-competitive so it's hard to stop that kind of reflex action of reaching out in desperation.

"A long time ago when Des [Hasler] and I first started working together, if you got done for a head-high tackle, Des would put you with me and we'd work intensively on agility.

"That's because we knew if you were sticking your hand out, you weren't in front of the person you were tackling.

"So for however long you were on the sideline [suspension] you were doing a tremendous amount of speed work and agility."

Pectoral tears seem to occur more often in the early season – Brown was round one, and so was Roosters winger Daniel Tupou last year.

Forwards also appear more frequently in the statistics.

"That's because they make way more tackles," Singe said.

Even though it is a reflex action, Singe says there are things that can be done in training to try to prevent too much strain being placed on the pectoral tendon. It's been thought too much bench pressing was to blame for fatiguing the tendon.

"It's not so much there's too much bench press, it is that there's not enough balance between posterior area work and your bench work," he said referring to resistance work needed for back muscles.

"More importantly you'd be looking at your loads and making sure players had plenty of rest between lifts, so you don't have an accumulated fatigue.

"If you're bench pressing and accumulated fatigue takes over, you might not complete the movement correctly and you add strain onto the tendon.

"When we look at our loading on that muscle group, we don't max-out our heavy lifting, heavy bench pressing. We look at a cycle of that strength work and out on the field we look at tackle technique – ensure their feet are in front of the person they're engaging. And don't extend your arms out."

Ibrahim said players themselves needed to be honest with medical staff.

"You tell players to look out for any type of strain or tendon tightness they might feel in the pec, particularly after a heavy weights session," he said.

"That's important to speak up and let us know. It's all about load.

"There is some specialised ultra-sound equipment that can pick up fatigue in a tendon ... it's probably the future in trying to predict who might get a ruptured tendon.

"But it's all fairly new stuff at the moment."