Rugby league has changed over the years but the power of the big hitters lives on.

Back in the early 1990s it was Wests' David Gillespie and Brisbane's Trevor Gillmeister leading the way when it came to bruising defence, while the likes of Paul Harragon and David Fairleigh were emerging as the prototypes of the new modern forward.

This article, titled "The Psyche of the Hitman", first appeared in Rugby League Week on February 24, 1993 and was written by Steve Crawley.

Defence, in American Football anyway, has become a blood sport, a new game of cheap shots and nastiness. Sad, but never sorry.

The hitmen of that game were recently invited to take off their helmets and defend themselves. It was a novel idea, sure, but at the end of the day their words were only marginally softer than their shoulder charges.

"Your job is to bring 'em down" said Philadelphia Eagles safety Andre Waters, reckoned to be the dirtiest bit of gear in the NFL.

"A defensive co-ordinator doesn't tell you how: he just wants 'em down."

The Los Angeles Raiders' Bob Golic added: "We (defensive players) meet at night. You know, we're like a cult. We hold underground meetings. We kill sheep... just kidding.

"The Raiders? We have no ethics. No morals. We're defensive guys. We're not allowed to have them. That's why we wear black jerseys. Because we're bad."

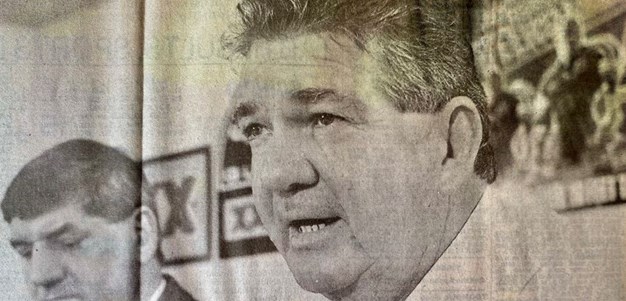

Western Suburbs' David Gillespie, like Golic, gets around in a black jumper and, again like Golic, he gets around pretty hard.

But the words of Gillespie and Golic, and the games they play, are worlds apart.

As a defender in Rugby League, Gillespie does not have the luxury – or crutch – of being able to retreat to the bench after wiping out an opponent. He must run the ball, too, face the music for 80 minutes. Our game does not allow the interchanging of attacking sides and defending sides.

In this game, there is nowhere to hide.

Still, as much as Gillespie cringes at the tag, he is a hitman, as soft as the nickname he carries around – "Cement".

"It was a trial against Manly back in '86," says Gillespie, "and that Charlie Haggett was still playing for them. I kind of put him into next week. They carried him off on a stretcher, but he wasn't hurt bad. I didn't maim him, nothing like that."

From the very beginning it should be noted that Gillespie is highly regarded by rival players. They know he is going to hit them, and hit them good, but – and this is where respect comes into it – he is not going to take a cheap shot.

And he is not going to race back to the dressing room and brag about the hits, either.

"We had this bloke playing for us (at Wests) who was running around telling everyone about his big hits," he says. "I pulled him aside one day and said, 'mate, you're just putting a big X on your head – if you don't shut up, you'll end up a target'.

"I'd rather talk about the tries I've scored, but I haven't scored that many."

Gillespie believes, as does Brisbane Broncos hitman Trevor Gillmeister, that the media plays a starring role in "tagging" certain players hitmen. Both say there might be half a dozen bigger hits made by other players during a game, but because they are "tagged", the oohs and the aahs of the crowd are louder and longer when it is their turn to rumble.

"Survey the fans," said bad guy Waters, back in Philadelphia, "and ask them what they like about football. They'll say hard hits, sacks on quarterbacks.

"If you don't believe me, try playing touch football and see how many people come."

Gillmeister, shorter than most forwards, but long in the lethal department, does his bit to pull the big Brisbane crowds.

"I get more of a kick hitting the big fellas," he says, "and one tackle I do remember was on Matt Goodwin a couple of years ago.

"Big hits are often on the borderline of being legal and illegal, and they have to do with timing. It doesn't matter what speed the bloke coming at you is going, if you're standing still... it's that last drive and getting your feet in the right position.

"I suppose a good hit will give the other blokes in the side a bit of a lift, but I get a lift out of it as well. At the Broncos we have blokes who can score 80 or 90-metre tries. I can't do that, so I've got to do the best I can."

Neither Gillmeister nor Gillespie, mind you, are simply defenders. They can't be, not in this day and age. A few years back a first grade side could carry a player who couldn't catch a ball, or another who couldn't tackle. No more. Rising stars like Newcastle's Paul Harragon and North Sydney's David Fairleigh can run, pass and hit with the best of them, complete footballers and prototype forwards going into the next century.

Harragon, in particular, came into the top grade perhaps too eager to be "tagged" but soon learned the way forwards do. The hard way.

"It's not that you try to take them out," said LA Raiders' safety Ronnie Lott, notorious as the hardest hitter in the States. "But that's the thing about sports now. It's like life. If you tell somebody on the field, 'I'm gonna take you out'," the first thing they believe is you're gonna hurt them. Just like life.

"Kids today say, 'I'm gonna get that guy', and most people think they're going to kill them. Not just beat 'em up like in the old days, but they're gonna shoot them with a gun.

"But the sad thing about sports is they think the same way. If I say, 'I'm gonna get that guy', I'm never going to get that guy to hurt him. What I'm going to do is give him my best shot. Now, if my best shot knocks him unconscious, then that's part of the game. But I'm not going there with intent."